It’s embarrassing being a part of the press corps these days

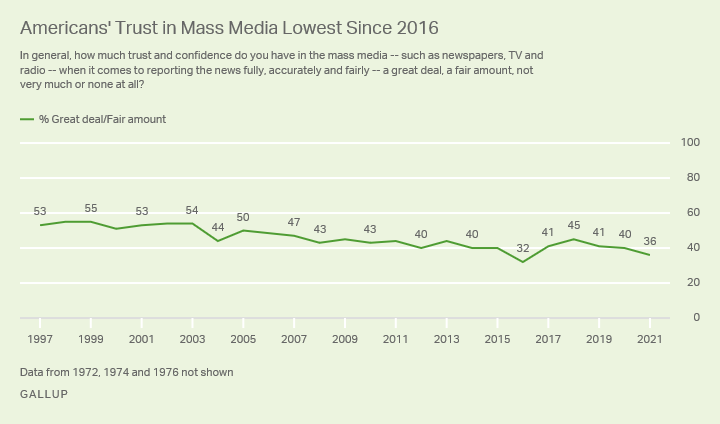

Dear press corps, this election cycle could be our last chance to serve the American people – we've already lost about half the country

It’s embarrassing being a part of the once-iconic Washington press corps these days. We’re failures parading about as conquerors. It’s a bit much. Just ask most Americans who have tuned us out or the half of the public who think we’re intentionally out to mislead them.

“Fifty percent of Americans feel most national news organizations intend to mislead, misinform or persuade the public,” Gallup and the Knight Foundation reported earlier this year.

That happened on our watch. What are we doing about it? Nothing, it seems. We’re focused on follower counts, likes, TV hits, book deals and promotions—all while perpetuating a broken system that has alarmingly alienated half of our neighbors. It’s a crisis.

It’s front and center, whether we recognize it or not. And it seems most political reporters have muted their critics, otherwise we’re all just tone deaf. Couldn’t come at a worse moment, as AI is well-positioned to replace tens of thousands of our jobs in the next couple years.

In the midst of—or, maybe, because of—the political and technological revolutions witnessed over the past few election cycles, we’ve continued business as usual. Americans have rejected our increasingly selfie-oriented personas, self-righteous tones and empty pop political coverage. Our sensational, herd-like reporting is easily replicated by bots, so now is the time—potentially our last chance—to try something new: we should make politics boring again.

Even as Americans are crying out to be heard, seen and reflected in Washington reporting, today’s press corps is unthinkingly reactive. We’ve become meme machines, as we reward congressional outliers with the spotlight they crave.

Americans seem to know we’re selling a myth.

And, sadly, many are fine living big little lies.

A few years back, a CNN White House correspondent told me and others in the Senate Radio-TV Gallery that he coaches his mom to only watch the network when he’s on at the top of the hour to protect her from the misleading punditry that fills the rest of the hour.

It’s not just going along to get on TV, a house, cars or whatever TV folks do with their “Trump bucks,” as at least one CNN executive called the network’s influx of cash in 2016 (according to what one of the best political reporters around told my students).

A flaw in the press—one that makes us stand out from our predecessors—is that few journalists know history these days. It shows.

I was so intimidated when I arrived in Washington, I bought the Complete Idiot's Guide to American Government! After quickly realizing I knew all that, I moved on to The House: The History of the House of Representatives by former House Historian Robert V. Remini.

There are few great works on Congress, but I wanted to know more. Every president has had to deal with lawmakers on Capitol Hill, so I then started reading a biography on every president before starting my MA in Government and Public Policy at Johns Hopkins University (where I’ve taught since 2016). While in the midst of the study, Josh Rogin and David Weigel asked me about my study within earshot of other reporters.

“I don’t think I’ve ever read a biography,” a writer for an online outlet with tens and tens of thousands of Twitter followers said, half to herself.

She’s now an editor. I have no idea if she ever felt guilt-tripped into reading a biography (and I don’t even like biographies! I just love Congress, hence the study), but lack of historical knowledge is regularly on display here in Washington.

In the lead-up to last summer’s select Jan. 6 committee proceedings, Watergate comparisons dominated the headlines. Even as the analogy was everywhere, it seemed off.

So I tested it by interviewing all 50 Senate Republicans in the 117th Congress and found there was no Watergate comparison. Turns out, only eight of Senate Republicans reported even tuning in, and 58 is far short of the 2/3rds needed to impeach. History matters. At least it used to.

Politics is people—and no, not AOC or MTG—or at least it used to be.

March 19, 1979 is a day that lives in infamy—it’s the day C-SPAN’s cameras first rolled live coverage of the US House of Representatives. Before then, few lawmakers even needed press secretaries, because few lawmakers mattered to a national audience. With precious little air-time, there was little noteworthy about one rank-and-file politician plucked from a sea of 535 of them.

After TV killed the radio star, 24-hour news came to town and made day-time television stars out of congressional backbenchers who the networks parade about as representatives of their parties, even as many barely even speak for their districts anymore, now that all politics is national.

When I arrived in Washington in 2006, CNN had two producers at the Capitol. They’ve now got at least three on-camera reporters—often accompanied by a producer and camera operator—roving the marble halls on most days. Hell, TMZ is now at the Capitol.

In 2016, reality TV star Donald Trump rewrote the rules, stripping press credentials from the likes of Univision, Buzzfeed, CNN, Washington Post, The Daily Beast, Des Moines Register, Politico, etc.

Back then, I tried to spearhead an effort for news outlets to band together and boycott Trump rallies until he reinstated each outlet. Leaders at the National Press Club went a different route; writing respectable letters, seemingly, from a bygone era. And it was one of the few ideas I ever had rejected by The Guardian, where I penned op-eds at the time (under my professor cap), which likely didn’t want its own reporter’s credentials to be yanked.

Trump then became president and it was too late: He’d already been allowed to rewrite the rules, and he’s continued to do so, using the bully pulpit of the White House and his social media feeds to redefine the nation’s press corps to millions.

In 2018, we sold Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and The Squad to viewers, while these days we’re chasing Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), George Santos (R-NY) and Lauren Boebert (R-CO). They’re not representatives of the House of Representatives; they’re brands and we, it seems, their greatest brand ambassadors, as we regularly sell them to our respective audience.

Heading into 2024, it seems many news organizations are tripling down on their failed 2016 playbooks, even as there’s one sweeping change they’ve failed to account for: We’ve lost the American people.

With trust in the media at historic lows and with AI here—likely already working on a command to rewrite all our similar headlines quicker and cleaner than our collective groupthink will ever be—it’s time to try something new, if vintage: leading with reality; not reality TV.

We’ve evolved into predictable, thus replaceable, memes.

We need to retire our self-righteous tones, in the realization that we’ve been tuned out. If anything, we should come from a place of humility, apologizing and begging forgiveness of the millions we’ve alienated.

An obvious way to do that is to go where our audience is. They’re not in the nation’s Capital. In fact, they’re barely even afterthoughts in today’s Washington. We can help change that by regularly reminding the nation’s politicians of the people they were elected to serve; not the interests they bow to.

There are now two Americas. Silicon Valley’s finest algorithms now view our work like the American people do: as left or right. We keep fitting their molds.

It’s time to break out of the molds we’ve made for ourselves and rethink Washington coverage, unless we’re content being the tropes we’re now dismissed as.

About me: I’ve been covering Congress since 2006 and teaching political communications at the Johns Hopkins University (MA in Gov’t) since 2016. I’ve previously been an op-ed contributor with The Guardian, Reuters, NBC Think and On Tap Magazine.

I think that was a really good article by you! I haven't watched the news since Trump was elected because of all the sensationalism and bologna going on! Good one. Matt

The search for truth is less profitable than the search for views.